Written by: John S on 2 July 2022Russian imperialism is certainly on the march, determinedly challenging the “unipolar” hegemony of the US and NATO.

The book “Russian Grand Strategy, in the Era of Global Power Competition” (ed. by Andrew Monaghan), is written by, and from the perspective of, western military strategists, and purports to understand Russia as a rival to the supposedly legitimate moral, political and military authority of the US/NATO. However, it still provides valuable information about Russian planning and thinking. And it does get behind the simplistic propaganda that explains all Russian aggressive actions as caused solely by the megalomanic arrogance of one man, Putin.

The authors all operate from assumptions about US/NATO legitimacy and superiority. One uses the trite cliche of the world “rules-based order”, which is just code for the legitimacy of continuing western domination. What rules? Who has made the rules, especially since 1945? In whose interests do the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organisation operate?

The hypocrisy of these assumptions was starkly exposed at a recent WTO meeting where the participants refused to end government subsidies for illegal fishing. Capitalist governments continue to subsidise commercial activities that they themselves have deemed illegal- so much for rules! This is in reality the anarchy of capitalism.

Overall Russian Strategy

Russia (and the book’s authors) recognise the world’s increasing instability and volatility, and the intensification of rivalry between the previously dominant US/NATO, and rising powers such as Russia and China. Russia recognises the threats to itself and China posed by NATO’s expansion of its self-declared remit. NATO has been expanding its scope beyond the North Atlantic; NATO forces helped to invade Afghanistan and to bomb Libya. The recent NATO meeting in Madrid included government leaders from Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand.

Russia sees the necessity of increasing its economic and politico/military strength, in order to protect its own frontiers, including its self-declared Exclusive Economic Zones, and to forward its economic and expansionist interests, across the whole globe. It has developed, and continues to develop, a range of economic, military and diplomatic strategies to further these aims.

It seeks not only economic and military strength and security, but also to establish itself as a recognised Great Power.

Economic Strategy

Russia has greatly expanded its internal exploitation of natural resources, especially hydrocarbons and of grains, and their export, particularly since around 2000. It has identified trade in strategically important goods as a key to profitability and strategic advantage. Russia is the largest exporter, or one of the largest exporters, of hydrocarbons, grain, armaments and nuclear power equipment.

Despite western sanctions (pre-Ukraine), Russia’s share of world trade in these strategically-important goods grew between 2010 and 2020.

Since about 2010, Russia has been shifting its trading priorities in these goods away from Europe, toward Asia, the MENA (the Middle East and North Africa) and Africa, in particular to China, India, the Stans and the Middle East. Its purpose is to

- get around US/NATO sanctions and economic blackmail

- enhance its political and economic independence

- access new markets in the face of increased US oil and gas production and predicted reductions in hydrocarbon demand in Europe because of its climate change strategies

- exploit the anticipated continuing and increasing reliance on fossil fuels in Asia, and

- feed off the economic growth of China.

Russia has a target of ½ of its energy exports going to Asia by 2035.

Russia’s role and influence as a gas and oil exporter has increased since 2000. Its exportable surplus (ie that available for export after internal needs are met) has increased over the past decade, while that of several competitors has fallen. It has coordinated with OPEC to avoid oil gluts and keep prices high. The dramatic increase in US shale oil production has complicated the world market, but US shale oil production costs are much higher than for Russian oil, so Russia is likely to outperform the US.

There is intense competition in the world gas market with Australia, Qatar and the US rivalling Russia. However, again Russian production costs are lower, and transport is easier through the system of pipelines to Europe. How this plays out during and after the Ukraine war remains to be seen. Russian Arctic gas production is in the process of ramping up dramatically, and Russia will be able to readily access growing Asian markets.

Russia has similar aims for its export of all parts of the nuclear fuel cycle, from involvement in uranium extraction through to reprocessing and disposal of spent nuclear fuel, targeting the same types of countries.

Armaments are exported, often on very favourable terms, to make money but also to cultivate friendly relations and influence with foreign governments. Despite sanctions, Russia is the world’s second-largest exporter after the USA, particularly to Asia (China, India and Vietnam are major customers), with MENA the second-largest area customer (especially Algeria, Egypt and Iran). This trade is likely to become more contested as rivals such as China, Turkey and India grow.

Russian policy is to maximise both its agricultural autarky(self-reliance) and the export of grains. In 2019, Russian food exports surpassed the value of all other Russian exports, excluding hydrocarbons. The main recipients were Saudi Arabia, Vietnam, India, Indonesia, the Philippines and North Africa. The diversification of trading partners is well underway. Russia is now the world’s largest wheat exporter. Russian wheat is cheaper to produce than its major competitors. Wheat exports overtook those of the US and Canada in 2017. With Australian wheat yields estimated to be falling due to the extra heat caused by climate change (by 27% between 1990 and 2017, according to the CSIRO as cited in this book) and US production flatlining, Russia is moving into new markets especially in South-East Asia. The objective of dramatically increasing grain exports (planned to double between 2017 and 2024) is specifically to make money and to exercise political influence and power.

State Monopoly Capitalism

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, there was a feeding frenzy of (mainly) ex-officials grabbing and privatising as much public property as possible. While public services collapsed and the population sank into greater and greater poverty, a few oligarchs, employing mafiosi extortion, ran a chaotic economy that saw Russian national wealth and power decline.

Since 2005, the state has adopted a strategy of nominating “national champions”, singling out leading enterprises in each industry for nationalisation or close governmental control. These are privileged with complete or largely monopoly status in their industry. These include:

- The oil companies Yukos and Sibneft amalgamated into the Rosneft oil and Gazprom gas monopolies

- Rostec, which owns some 700 military equipment enterprises

- United Shipbuilding Corp which owns most Russian shipyards

- Rosatom, which has a virtual monopoly over all nuclear power, weapons and exports

- The VTB bank, which took control of most Russian grain marketing and transport in 2019.

This monopolisation provides massive profits to a very narrow ruling capitalist class and their bureaucrat partners. It also represents a marriage between economic and political power.

This state of state monopoly capitalism has enabled Russia to set, and make progress in, planned strategic economic, political and military objectives.

In the 1990’s, Russia was weak, chaotic and on the defensive.

Since 2000, Russia has been attempting to integrate its security and economic objectives and actions. Despite many ups and downs, Russia has made some progress, especially since 2015, in developing coherent strategies for coordinated economic and military development.

This progress has been rather stymied by the inertia of existing power and institutional structures, a degree of economic stagnation (despite export successes) falling living standards and decreasing popular support for, and trust in, people’s material prospects.

Overall, Russia has progressed its integrated strategic outlook and planning, with some successful implementation, (probably with greater effect than western nations) but is also restricted by the typical vagaries and chaos that are essential characteristics of a capitalist system.

Military and Geographical Strategies

Mapping

Russia has invested heavily in mapping, especially the world’s oceans and sea routes.

It developed its own satellite mapping system in advance of the US, with receiving stations in Brazil, Nicaragua, South Africa and Antarctica. The information and detailed cartography are to be utilised for commercial and military purposes. It has recently been utilised in military activities in Syria, for example.

The Northern Sea Route

Russia is attaching huge importance to securing control of the Northern Sea Route (NSR), between the Russian mainland and the Arctic.

It has been angling for complete and exclusive control for security reasons. Since 2014, it has increasingly restricted access to other nations’ shipping and requires escort by Russian ice-breakers, despite US and NATO objections. It has constructed huge dual-purpose ports across the NSR- ports that double as naval bases and export points particularly for gas.

It sees the NSR as a key export corridor to Asia. It has built a huge ice-breaker fleet, including the most powerful ship in the world (with more of them to come). Production has begun on even bigger ones. These, and the impact of ocean-warming and the melting of the Arctic ice, are predicted to make the NSR navigable all year round, hugely increasing Russia’s export capacity to Asia.

Militarisation

Russia, like other imperialist powers, is engaged in frantic expansion and development of its military capacities.

It has analysed the continuing development of military technology, which, over thousands of years, has gone through several technological stages:

- Edged weapons

- Gunpowder

- Rifled weapons

- Automatic weaponry

- Nuclear

The current sixth stage comprises precision-guided weapons, the weaponisation of information technology (cyber warfare), including propaganda and psychological warfare, and the supposedly decreasing importance of ground forces. This stage is evidenced by the facts that, in World War 2, it typically took 4,000 air sorties and 9,000 bombs to destroy a bridge; in Vietnam the US used 200 bombs; but in Yugoslavia in 1999, it took one aircraft firing one cruise missile. Drones have since taken this process further (though with frequently imprecise killings of innocent civilians). The current imperialist military orthodoxy assumes that the mass destruction of enemy infrastructure makes the taking and occupation of enemy territory unnecessary as a primary strategy.

The imperialists envisage a seventh generation of “ecological” weapons disrupting natural ecosystems, involving, for example, public health, environment, and water supplies, becoming operational sometime around 2050 - yet another reason to get rid of imperialism ASAP.

Current Russian military technology is constantly developing, and in some cases, is well ahead of the US/NATO, eg the S400 surface-to-air missile system, currently being purchased by NATO member, Turkey.

Russia’s emphasis on the importance of trade necessitates a focus on the world’s oceans, trade routes and factors affecting shipping.

Naval power has assumed top importance.

In 2015, Russia determined to develop a presence in all oceans, as a key part of its “geo-economic” rivalry with other powers. It prioritised the “near seas” -the Atlantic, Baltic, Mediterranean, Black and Caspian Seas; and, of course, the Arctic. It is also projecting itself into the South Atlantic, the Indian, and even the Antarctic Oceans.

The Russian navy has shown the flag in countries such as India, Indonesia and the Philippines, which are all target countries for increased Russian exports, especially hydrocarbons.

Planning documents cite the intensification of “great power” rivalries, and Russia intends to maintain and increase its access to resources and markets, and to protect its trade routes across the whole globe. It has embarked on a program of naval modernisation, modernisation of naval and merchant ports (often the same thing), huge increases in naval and merchant shipping capacities, and the development of human capital, in areas of training, safety and salaries. A 2019 document identified weaknesses to be overcome:

- An inadequate industrial base

- An outdated civilian nuclear fleet

- Low levels of maritime transportation

- The poor state of the civilian fishing fleet

In 2019, Russia adopted a whole-of -government approach to advance its maritime strength, involving the ministries of Defence, Economic Development, Transportation, Natural Resources, Foreign Affairs, Education and Agriculture.

Since 2008, port capacity has doubled, and turnover is increasing, often at the expense of neighbouring rivals. In the Baltic, gas pipelines and new transportation hubs for oil, fertiliser, coal and grain have taken much business from the ports of the Baltic states. Similarly, Russian ports in the Crimea have undermined business in Georgian and Ukrainian ports.

Russian imperialist expansion and aggressiveness has all the hallmarks of any imperialist power. It ploughs huge resources into constantly expanding economic and military capacity and activity, in order to advance and protect its access to resources and markets, and to contest any threat or competition. It endeavours to plan and act strategically, but is always hamstrung by the vagaries and chaos of capitalist financing, economic ups and downs, and internal ecopolitical rivalry.

When it acts, it is typically brutal and clumsy. Witness the attack on the Ukraine, designed to warn and intimidate the US/NATO from extending its reach east toward and around Russia. It has shot itself in the foot, as Sweden and Finland have now opted to join NATO, and Ukraine and Moldova are being fast-tracked for EU membership, and Georgia’s chances of the same appear to be improving.

How the attack on Ukraine will play out, economically and militarily, remains to be seen. It has certainly revealed weaknesses in Russian military effectiveness. It also exposed the typical callous brutality of imperialist powers as they bomb indiscriminately to try to cower a population into submission. Also problematic will be how and how much Russia can get around US/EU sanctions, continue to export massive amounts of gas and oil to Europe, and develop and access Asian markets.

Russia’s banking on Asian markets for hydrocarbons holding up as climate change forces all, but especially, European markets to transition away from fossil fuels, may also prove either completely illusory, or of only short-term benefit.

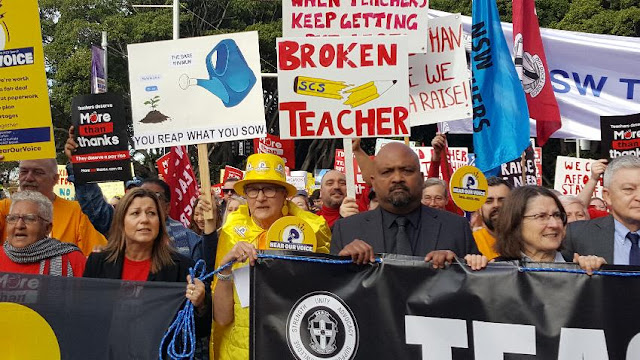

The intensification of world imperialist rivalry, of which Russian eco-military policy and development is an important part, is leading to more, and more dangerous, conflict, often via proxies such as Ukraine. The US is desperate to maintain its sole superpower status and its position as the world’s prime exploiter. It is lining up its allies and minions like Australia to back it militarily. Many other nations are breaking through and away from this control and are carving out their own slices of economic activity and exploitation. The drums of war are beating more and more loudly.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)