Written by: Nick G. on 20 May 2024

One evening in 1970, a tall, sandy-haired young man came down the stairs to the basement of the Adelaide Revolutionary Socialists building in Dequetteville Terrace, Kent Town. It was surprising to see him there as he was not a revolutionary but a well-known member of the Labor Party and of the pacifist-aligned Campaign for Peace in Vietnam.

One evening in 1970, a tall, sandy-haired young man came down the stairs to the basement of the Adelaide Revolutionary Socialists building in Dequetteville Terrace, Kent Town. It was surprising to see him there as he was not a revolutionary but a well-known member of the Labor Party and of the pacifist-aligned Campaign for Peace in Vietnam.

What was more surprising was the handgun he was carrying, which he proceeded to show to his friend Rob Durbridge, leader of Students for Democratic Action at Adelaide University.

Why he had the gun, and what he later did with it, I’ve never known, but it didn’t impede his political career. Three years later, he was elected to the SA Parliament, and two years after that, at age 29, was sworn in as the State's Attorney-General.

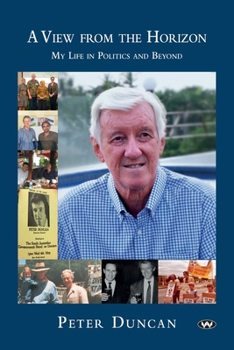

Several days ago, I attended the launch of his book of anecdotes and memoires, A View from the Horizon.

Peter Duncan, the author, was later elected to Federal Parliament in the Hawke-Keating era.

He is justifiably proud of his record as a reformist social-democrat although it was never his intention to do away with capitalism: his legislative achievements were all in the area of social policy and did not, nor could have, done away with the economic base of capitalism.

Still, working with a premier who wore pink shorts to Parliament, he was able to achieve the abolition of capital punishment, the abolition of drunkenness in public as a crime, the criminalisation of rape in marriage, the abolition of legal consequences for illegitimacy, recognition of de facto couples, the criminalisation of racial discrimination and drug law reform. But it was his Private Member's Bill, the first in the world, to decriminalise homosexuality and establish equal rights for homosexuals with heterosexuals for which he is best known.

As a reformist social-democrat, Duncan is scathing in his book about the SA Labor governments that came after his and Dunstan's. He writes:

Some people may not be aware of the phrase 'went to water': its origins lie literally in what happens to ice when it melts from a robust solid state to a malleable and wet state. My comrade, Bob Mac, wittily observed that it must have been extremely hot in those Labor Cabinets under Bannon, Rann and Weatherill, because when good people entered those Cabinets, they 'went to water'. Sentiments I endorse entirely.

Later he writes:

Labor government either try to reform society or to manage it. Unfortunately, in the past 40 odd years, the managerialists have held sway. They could just as easily have left it to the Liberals.

It would be unfair to say that these views reflect illusions about capitalism. Both reformism and managerialism accept the permanence of capitalism and the legitimacy of bourgeois parliaments as the sole avenue for both reformism and managerialism. Duncan's post-political forays into business ventures, also examined in the book, illustrate his acceptance of capitalism.

Duncan was one of the few Australian state politicians to successfully move to the federal sphere. He was the federal member for the SA seat of Makin from 1984 to 1996, holding several ministerial positions under Hawke, but having any real influence blocked by the powerful Right and Centre Left factions of the ALP.

One of his first blues with Hawke, a cigar smoker, was over a ban on cigarette smoking on domestic airlines. Duncan gave his Transport ministerial support to a private member's bill introducing the ban. He writes:

…Hawke was furious and carpeted me, to no effect…Hawke’s anger must have been on behalf of the tobacco lobby. Of course, if he had ordered a backdown from what was a very popular initiative, it would have looked as if he was under the thumb of the tobacco lobby, which was the case, since they were significant donors to the ALP at that time.

In the same year, 1987, he recalls going into Hawke's office as the PM was on a special red phone call to transport boss Sir Peter Abeles, long acknowledged as a personal friend of Hawke. He "told Bob that as one of his ministers, I wouldn't mind having that 'red phone number', to which Hawke replied agitatedly, ‘

'And when you’ve done as much for me as Peter Abeles, you’ll be entitled to it'."

Duncan had been summonsed by Hawke to explain why his department had awarded a contract for northern coastal surveillance, on behalf of Customs, to a small operator, Amann Aviatics. The contract had previously been held by Sky West, but Amann had the superior bid and had won.

Unknown to Duncan, Sky West had been bought cheaply by Abeles who was furious to have lost the government contract. Hawke and Gareth Evans fabricated a narrative about Amann being unable to fulfil its contract which conflicted with the department's legal advice. According to Duncan, Abeles "lobbied Hawke to get the Amann contract rescinded" and that Hawke "colluded in this perfidy". A subsequent High Court challenge by Amann upheld its right to the contract.

This is not the only example of Hawke using an official position to look after, and curry favour with, influential capitalists. Duncan records that in 1975, when Hawke was still president of the Australian Council of Trade Unions, he brokered a deal between Rupert Murdoch and Jimmy Hoffa, notorious boss of the Teamster's Union in the USA, to transport Murdoch's new US newspapers across the USA at a rate which undercut his competitors.

What grease was used to achieve this deal and what benefit Hawke obtained, I have no idea. What is clear that the leader of the ACTU at the time facilitated a deal that cut US workers' income and conditions.

During his book launch, which included a discussion with friend and former SA Premier and Vietnam Moratorium Committee leader Lynn Arnold, Duncan was only once interrupted with spontaneous applause. That was when he volunteered his view that SA’s anti-protest legislation, introduced by the Malinauskas Labor government, was "despicable". It was a strong statement, made in the presence of the current Attorney-General, Kyam Maher, who had overseen the lifting of penalties for "obstruction" from $750 to $50,000 and up to three months' gaol.

Two nights later, on May 16, on the anniversary of the rushed, overnight passage of the anti-protest laws, police arrested eight people who were among hundreds who occupied and held a sit-in at a city intersection to protest the legislation.

Significantly, and as a measure of popular opposition to the anti-protest laws, the eight were not charged under the new obstruction legislation, and were each fined only $156.

The task of removing the "despicable" legislation still remains.

No comments:

Post a Comment